Synthwave existed contentedly for over a decade with little or no confusion about the fact it was a separate form of music from synth pop. However, as synthwave has evolved deeper into vocal-based songwriting in recent years, it's become increasingly common for fans and artists to begin using the two names interchangeably. Along with the conflation of terms has come confusion about how synthwave is different, if at all, from synth pop.

From a historical perspective, it's easy to understand why synthwave isn't synth pop. They are each their own rich genres of music with thousands of contributing artists, and the terms are not simply catch-alls for music made with synthesizers or synth-based music with vocals. With few real exceptions, synthwave and synth pop are separate genres of music with strikingly different backgrounds.

What's in a Name?

Using the terms “synthwave” and “synth pop” interchangeably obscures understanding of the music. This makes it more difficult for fans to locate music that appeals to their specific tastes, generates confusion in conversations, and glosses over important creative differences between artists in both genres, disregarding decades worth of beloved synth pop and synthwave creations in the process.

Importantly for creators of synthwave music, adopting the older and generally unrelated term “synth pop” makes it more difficult to connect with interested fans and build an engaged audience. Fans of traditional synth pop are not necessarily likely to enjoy synthwave, which leads to misspent advertising money and unnecessary legwork that could be avoided by sticking with the increasingly prominent and recognized “synthwave” label, which represents a vibrant and specific niche of music.

Making a distinction between terms is also relevant for listeners. As with all art appreciation — as well as appreciation of food, wine, birdwatching, and an endless number of other things in life — category labels are a fundamental element of recognition and comprehension. When used flexibly and as a means of description, they are an indispensable tool for understanding and communicating with one another about our shared experiences with music, enhancing our enjoyment of it in the process.

This article is rooted in a firm belief in the importance of music genres. It is meant to clarify and embrace creative differences between artists, and it recognizes that genres exist on stylistic spectrums with different shades and combinations. As such, it is often relevant to describe the style of individual songs with more than one adjective and genre term, a fact that will be evident throughout this article.

Despite the understandable confusion over similar names, the differences between synthwave and synth pop are quite easy to hear, and there are decades’ worth of examples of synth pop music for us to explore.

What Is Synth Pop?

To understand how and why the genres are different, it’s of course necessary to establish what each of them is in the first place. I've already written a full history of synthwave along with descriptions of its subgenres in What is Synthwave?, so if that genre seems murky or unfamiliar, check there first. This article will primarily focus on synth pop in order to make the differences between the two plain to hear.

Note that the goal of this article is not to detail the complete history of synth pop, but to pinpoint its most prominent and readily identifiable characteristics in order to establish an identity for the genre and use it as a means of comparison to synthwave.

Synth pop is one of the earliest forms of electronic music, and like almost all electronic music, has its roots in the work of the German group Kraftwerk in the 1970s. However, as with many music pioneers, much of Kraftwerk’s early music falls outside or on the edges of the genre they helped pioneer (much as Black Sabbath’s releases from the 1970s were not yet heavy metal).

Instead, the best examples of synth pop from Kraftwerk came later, particularly on the group’s 1986 album, Electric Café. In fact, it’s worth jumping ahead momentarily and pinpointing “The Telephone Call” from that album as a notable example of true synth pop music.

Genres are based on patterns, which means that dense areas of common creative elements form the heart of genres while less common approaches and techniques form the edges. When synth pop is viewed broadly with decades’ worth of contributions in mind, “The Telephone Call” lands very near to the center of the synth pop style.

While listening to “The Telephone Call,” note the stiff, mechanical beat, machine-like effects and melodies, and dispassionate, spoken vocal delivery, as these are all essential aspects of synth pop music and crucial points in this discussion of the genre.

True synth pop from the fathers of electronic music. Kraftwerk, 1986

Early synth pop

Although much of ‘70s-era Kraftwerk was not yet synth pop in its full sense, the group helped to spark a growing interest in synthesizers as instruments, an interest that was shared by young artists in the UK in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. It's there that synth pop (originally hyphenated as “synth-pop”) developed a stronger identity and first established an identifiable pattern of music.

Among the earliest and most notable pieces of British music to shape the synth pop sound are Gary Numan’s “Cars” from 1979, as well as Human League’s “The Things That Dreams Are Made Of,” Ultravox’s “The Thin Wall,” and Depeche Mode’s “New Life,” all from 1981. Once again, note the rigid and minimal rhythmic elements, sparse production, and partially spoken vocal delivery in each of those songs.

An upbeat, early synth pop track from genre pioneers Depeche Mode, 1981

Many of Depeche Mode’s most popular early songs lean toward a more energetic style of music than other synth pop creations, though they share all of the genre-identifying characteristics mentioned for “The Telephone Call.”

Synth pop’s defining elements — mechanical rhythms, understated compositions, spoken vocal deliveries — were the result of a few different factors, including the performers’ modest technical skills and the limitations of the early synthesizers available to them. However, in many cases, the music was also a reflection of the creators’ underlying conceptual interest in machines, with synthesizers frequently represented as the instrument of artificial lifeforms.

That aspect has remained a vital characteristic of the synth pop genre throughout its history, and it’s plain to hear and see in the performances of songs that planted seeds for the entire genre, including Tubeway Army’s “Are Friends Electric” and Kraftwerk’s “Das Model” of the late ‘70s.

In the case of Kraftwerk — who wrote songs with titles like “The Robots” and “The Man Machine” — the members literally performed their music as though they were androids. (This robotic aspect of the band’s performances, as well as its relationship to German minimal art culture, was famously parodied in Mike Myers’ Sprockets skits using a sped-up loop of Kraftwerk’s “Electric Café” for the theme music.)

The mannerisms of the performers as well as the relative style of the music are echoed in Tubeway Army’s “Are Friends Electric” from 1979. “Are Friends Electric” is a rock-based precursor to true synth pop, and although it does not represent the genre as fully as “The Telephone Call” or even Gary Numan’s “Cars” from later in 1979, it is an essential part of the genre’s genesis and exemplifies nearly all of its defining characteristics. The music’s icy atmosphere, minimalist delivery, and Numan’s android-like performance in the video below make this an immediate and vital example of synth pop’s origins.

A formative example of early British synth pop. Tubeway Army, 1979

https://youtu.be/QzSM3pRtgcM

This interest in machines, both directly through the electronic instruments and indirectly as part of culture’s increasing shift into computer-based society, results in a very rigid sound that is present in all true synth pop music. A crisp, often forceful 4/4 rhythm combines with emotionless vocals and punctuated melodies for a sound that feels like it was written and performed by synthetic life forms.

As the style developed a clearer identity in Britain at the start of the new decade, its early sound was embraced and began to flourish more widely back in Germany. Excellent examples of this come from The Twins, who released Passion Factory in 1981 and Modern Lifestyle in 1982. Both albums feature songs with unmistakable similarities to the early synth pop explored by British acts at the time, including the minimal, robotic sound of the music along with semi-spoken vocals.

Early German synth pop from The Twins, 1982

Creations from the first several years in synth pop’s history are particularly sparse and free of embellishment, and it’s often relevant to recognize them as their own form of “early synth pop” music, especially as the style has undergone its own careful and explicit revivals. For example, artists like Sector One, Datapop, and Unisonlab have created early synth pop music in the 2010s with strong influences from Kraftwerk recordings of the late ‘70s.

(Jumping ahead slightly, it’s worth observing that this revival of early synth pop music is drastically different in terms of style from synthwave, which is not an explicit throwback to any particular form of music from the 1980s.)

Early synth pop from Britain and Germany — accented by experimental synth creations from Yellow Magic Orchestra in Japan — form the foundation of the genre. However, it’s worth mentioning again that the recordings from the late ‘70s and early ‘80s were later pushed to the edges of the synth pop genre as the pattern of music expanded and concentrated more heavily on a slightly evolved sound, epitomized by Kraftwerk’s “The Telephone Call” from 1986.

Early Synth Pop’s Broader Context

In the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, synth pop was fundamentally a subgenre of new wave, which referred to a massive cultural shift in songwriting styles coming from Britain, and shortly after, the US. There are several distinct facets of new wave, and the label is more relevant as a descriptor of music innovation from the era than for a particular creative approach. That said, new wave can very generally be described as a melodic, rock-based evolution of punk music.

Synth pop began as a specific style of this new wave revolution and later evolved into its own complete genre. However, because of the interrelated nature of the two, there is a significant amount of gray area between synth pop and new wave throughout the ‘80s. Artists often leaned toward one style or the other, even fluctuating from one track to the next on the same album.

Ultravox’s “We Came to Dance” from 1982 is a clear synth pop song with its no-frills composition and stiff delivery, while the song that precedes it on the group’s Quartet album, “When the Scream Subsides,” is a new wave track driven by an electric guitar and a powerful vocal performance by Midge Ure. Robert Palmer, the decade’s master of pop music experimentation, embraced the minimal early synth pop sound with his 1980 hit “Johnny and Mary,” while the very next track on his Clues album, “What Do You Care,” is a funk-driven rock piece that more closely recalls his recordings from the ‘70s.

Early British synth pop from genre chameleon Robert Palmer, 1980

Naturally, the interrelated nature of new wave and synth pop led to much of the later historical confusion around synth pop, with artists like Duran Duran receiving the label despite their music predominately being an elaborate style of upbeat rock music with warmly melodic vocal hooks.

This confusion was further compounded in the ‘80s as early synth pop was incorporated into a larger melting pot of commercial music that blended the characteristics of synth pop and new wave with funk, soul, hip-hop, and a high number of other styles. As the genres evolved into newer and increasingly unrelated styles, a lack of new and meaningful terms allowed the synth pop label to be passed along indecisively to new genres.

The Pointer Sisters’ 1984 album Break Out is a great example of this melting pot of music ideas, and it contains previously unrelated genre elements like R&B and synth pop alongside one another on the very same songs. Despite the influences of synth pop on the album, however, none of the entries on Break Out can be properly classified within the genre, and it is more accurate to refer to the recording as “‘80s commercial Pop” or simply “‘80s Pop.”

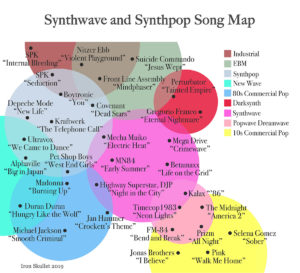

The following genre map is helpful as a visualization tool for understanding how synth pop, new wave, and ‘80s commercial pop are interrelated, but often separate genres of music. Note that it is impossible to fully categorize genre evolution in this way, and so the diagram is meant as a visual reference and not a complete classification system.

It’s worth revisiting the topic of ‘80s pop later, but while mainstream culture was adopting pieces of synth pop for its own purposes, the cold, robotic heart of the music continued to connect itself with a very different culture and style of music, particularly in Germany and its surrounding countries.

Synth Pop, Industrial, and Dark Wave

Significantly, synthesizers were often frowned upon by the established music world of the late ‘70s. They were not serious musical instruments in the eyes of many professional songwriters, producers, and critics of the era, and so the artists who embraced them — and the venues and labels who supported the artists — often held a counterculture mindset and dedication to underground music.

This meant that early pioneers of synth pop frequently shared their performance spaces with post-punk and industrial musicians, a fact with immense implications for the future of multiple genres.

For those who are familiar with synth pop and industrial music, that fact will immediately connect the dots in the ancestry of those genres, including their sound and visual aesthetic. Synth pop and industrial music have shared their DNA in each other’s creations for decades, and they have similarly carried their punk heritage with them across the years, as in rivethead culture.

Soft Cell is a famous example of a synth pop act who exhibited the genre’s lingering ties to punk culture. Another example is the German group Boytronic, whose synth pop track “You” from 1983 perfectly represents the triangular relationship of synth pop with industrial and post-punk music. The cold, mechanical rhythm of “You” borrows from the percussive sting of industrial tracks while the punk and post-punk influences shine through in the vocal delivery and aesthetic of the music video.

German synth pop with close ties to industrial and post-punk. Boytronic, 1983

Boytronic produced numerous examples of synth pop in this style, including “Diamonds and Loving Arms,” “Luna Square,” and “Photographs,” all of which feature a leaden atmosphere with sharp percussion, robotic synthesizer tones, and unsmiling, semi-spoken vocals.

To fully understand the close relationship between synth pop and industrial music, it’s worth examining the work of industrial pioneers SPK. When the group released their Machine Age Voodoo album in 1984, it was a marked departure from the experimental industrial noise they made on earlier releases like 1982’s Leichenschrei. Instead, the recording incorporated elements of the synth pop style that was rapidly gaining momentum in the first half of the 1980s.

The result is tracks like “Seduction” that feature a vicious, striking rhythm with detailed percussion and prominent vocal leads, all delivered with steely production. These creations perfectly represent the deep bond between industrial and synth pop music in the emerging years of both genres.

A hybrid synth pop-industrial creation from industrial pioneers SPK, 1984

Because of their close genesis alongside one another in underground clubs, it’s accurate and relevant to think of synth pop and industrial music as fraternal (non-identical) twins. This tight, nearly inextricable relationship between the two has persisted without interruption for 40 years.

Crucially, true synth pop music always bears a mechanical, robotic edge, and more often than not, percussive elements with an industrial touch. The more a music creator disconnects from this mechanical sound, the harder it becomes to classify their creations as synth pop.

This melting pot of creative ideas between synth pop, industrial, and post-punk music will also be familiar to fans of dark wave (not to be confused with dark synthwave, aka darksynth), which emerged from the same underground creative spaces. As post-punk evolved into increasingly diverse forms of music like dark wave, it frequently brought the synth pop and industrial twins with it.

For example, dark wave pioneers Clan of Xymox’s self-titled album from 1985 carries clear examples of its relationship to synth pop, particularly on the songs “Stranger” and “No Human Can Drown.” Synth pop and industrial elements are present in an evolved, modern form on the act’s newer tracks like “Your Kiss” from 2017. Wolfsheim’s 1991 song “The Sparrows and the Nightingales” is another excellent example of a dark wave track that can be fully classified as synth pop.

Dark synth pop from Germany’s Wolfsheim, 1991

During the ‘90s and ‘00s, synth pop’s relationship with dark wave and industrial music became especially visible within the context of the ever-expanding EBM culture and several of its subgenres and outgrowths. For example, many future pop creators incorporated a direct and immediate evolution of synth pop music into their songs, bringing along touches of dark wave and industrial.

Several of Solitary Experiments’ songs from the ‘00s capture the essence of this mixture well, adding modern production touches and EDM sensibilities to the blend, as on “Delight.” As with many synth pop creations, “Delight” contains a dispassionate, android-like vocal delivery along with a stark, industrial-spiked rhythm section.

Dark synth pop with future pop production. Solitary Experiments, 2005

Covenant’s “Dead Stars” has a lighter tone than “Delight” but is a modern synth pop song by every definition, including its rigid and forceful 4/4 beat, dramatically robotic synth melodies, and sterilized vocal delivery. Another excellent example of this direct, future-minded evolution of synth pop is Colony 5’s “Heta Nätter” from 2005. Despite the updated production on the track, its ties to pioneering synth pop creations are unmistakable, and because “Heta Nätter” has a direct and immediate stylistic connection to early ‘80s synth pop from Depeche Mode, it is fully accurate to classify it as a synth pop song.

Synth pop with future pop production. Colony 5, 2005

So, Why Is Everything Else Called Synth Pop?

Although synth pop blends evenly into many different styles of music, its defining characteristics are often easy to identify. Yet the term is applied to an enormous range of music whose creations often hold no stylistic connections to one another.

Like many other popular music genres – such as heavy metal – fans, journalists, and musicians continued to use the term “synth pop” to refer to new forms of music that developed well beyond the genre’s signature sound. As mentioned earlier, this is largely due to its close connection with new wave music and the ways in which synth pop and new wave were incorporated into popular music of the 1980s.

As a result of the rapid creative evolution around the style and the failure to create or embrace new terms, “synth pop” became an increasingly broad and ambiguous term. Once the name became unmoored from its original sound and was carried into mainstream pop of the ‘80s, it began to float around in general public consciousness without anything concrete to attach itself to, and so new fans and creators began assigning it to unrelated genres without understanding what it meant or where it came from.

The result is that artists like Thompson Twins and Howard Jones are sometimes placed under its banner, despite them making music that is better defined as “new wave” or better still, “‘80s commercial pop.”

Although this misconception of synth pop sometimes reaches extremes (as we’ll see later with synthwave artists), there are plenty of gray areas to justify the confusion. Madonna’s first two albums, for example, show unmistakable influences from synth pop. “Burning Up” from her 1983 debut holds a strong connection to synth pop with its stiff, synthetic rhythm, though it would be difficult to fully classify it under that label, as the music is largely disconnected from the robotic, understated feel of the genre. Instead, notice the friendly, inviting production tone and hook-heavy singing style of the track below.

‘80s commercial pop with synth pop influences. Madonna, 1983

Once again, it’s much more accurate to identify the song as simply “‘80s commercial pop” or “‘80s pop.” Although a name like “‘80s pop” may sound generic, it’s actually fully relevant as a genre descriptor and represents the melting pot of ideas that was happening at the time. ‘80s pop artists came from very different backgrounds, though they gravitated toward a central music idea and created a diverse but creatively harmonious genre of music.

Pet Shop Boys provide another example of an artist blending synth pop with outside styles, and their music is a significant source of confusion over the term. Although the duo’s earliest tracks like “West End Girls” are clearly synth pop-related, the music is missing some of the rigid, android-like tone of the genre and favors a more accessible, commercial sound. Where the real confusion sets in is on later releases, as the act rapidly shifted away from their synth pop roots and began incorporating stronger dance influences, free-flowing melodies, and other distinctly different elements for a remarkable new sound.

This is plain to hear on Pet Shop Boys’ 1987 track “It’s a Sin,” whose lush instrumentation, sweeping orchestra, powerful vocal delivery, and rich production style pull it remarkably far away from synth pop.

‘80s pop and dance music with distant roots in synth pop. Pet Shop Boys, 1987

A similar type of evolution can be tracked within the discography of Depeche Mode, who by 1990’s Violator album had shifted into a more graceful style of music that aligned with commercial pop of the era and was difficult to classify as synth pop. This type of shift within a single artist’s discography is far from rare, particularly among music artists who find widespread commercial success. (For example, Judas Priest was arguably classifiable as hard rock in the late ‘70s, heavy metal in the early to mid-‘80s, and power metal by the time they reached 1988’s Ram it Down and 1990’s Painkiller.)

Numerous other artists from the era, including Alphaville and Eurythmics, fall into similar creative spaces as Pet Shop Boys, crafting detailed compositions with diverse instrumentation and powerful vocal leads that are only partly related to synth pop. In spite of the fact they are often associated with the term, none of their songs fit cleanly within the synth pop genre.

The rapid evolution of creative styles during the '80s ultimately caused the name “synth pop” to float around among unrelated music styles for decades, frequently causing confusion whenever it turned up. Synthwave is simply the latest form of music to inherit the synth pop label without owning a direct and immediate connection to the genre.

Is Synthwave the Same Thing as Synth Pop?

Synthwave is not the same genre of music as synth pop, nor is it a subgenre of synth pop. It is also not a revival of the older genre.

Once again, there is a full history of synthwave available here, but for the purposes of this article, it's enough to say that synthwave largely grew out of EDM of the mid-‘00s, and it tends to have softer percussion and bright, detailed melodies with a warm production style. Its pioneering creations pull heavy influences from funk, disco, and the original form of electro (think Herbie Hancock's "Rockit"), as well as from film scores and video game soundtracks. The sparse, mechanical aspects of synth pop, as well as its steely production, are absent from synthwave-defining creations like Mitch Murder’s “Midnight Mall” from 2010.

Instead, note the prominent and elaborate bassline, nuanced percussion, and diverse melodic touches in the song below.

True synthwave (outrun) music with minor similarities to synth pop. Mitch Murder, 2010

It’s true that some early synthwave releases like those from Miami Nights 1984 and Lost Years are at least peripherally related to synth pop, though in the early and mid-2010s their creations were virtually never mistaken for the older genre. It’s roughly accurate to think of synth pop and outrun (the original form of synthwave music) as musical neighbors, living on the same block and waving to each other in passing, but rarely ever sharing direct conversations with one another.

True synthwave (outrun) with minor similarities to synth pop. Lost Years, 2013

The strongest similarity between most outrun and synth pop is the 4/4 time signature and crisp rhythmic elements that appear on many songs in each genre. However, these elements are widespread throughout many forms of music, including unrelated ones like jazz and folk rock, and alone are not a strong basis of comparison. If they were, Bob Dylan’s 1985 track “Tight Connection to My Heart” and Bon Jovi’s 1986 hit “Livin’ on a Prayer” would be synth pop songs.

The current confusion over the synth pop name seems to stem from the increasing prevalence of vocal tracks within the synthwave genre and the shift away from linear song structures into pop formats with distinctive verse and chorus sections. Although it seems logical to combine "synthwave" and "pop" to “synth pop” or simply to connect synthwave with vocals to the ambiguously used name for the older genre, this is often done without realizing the depth and extent of synth pop’s history as a specific style of music.

In a distinctly ironic twist, the most popular artists making the shift into pop music, such as The Midnight and FM-84, are actually evolving away from synth pop and into a soft, commercial style of the late 2010s that holds no meaningful connection to the sounds of synth pop.

A dreamy blend of synthwave with indie pop. The Midnight, 2018

Not only is this music fully disconnected from synth pop, but its ties to traditional synthwave have become increasingly thin as well. In contrast with early synthwave, which borrowed heavily from ‘80s music culture like Euro disco, electro, and video game soundtracks, acts like The Midnight and FM-84 increasingly turn toward contemporary forms of EDM and commercial pop music for inspiration, combining modern mainstream sounds with retro synth tones for a unique and fresh blend of styles.

Compare songs like The Midnight’s “Lost Boy,” The Bad Dreamers’ “New York Minute,” or FM-84's “Bend and Break” to any of the synth pop examples in the section above, such as Kraftwerk’s “The Telephone Call,” and the differences are remarkable. FM-84's collaboration with Ollie Wride on “Bend and Break” is an excellent example of a synthwave song with pop vocals that holds no connection to synth pop music.

Synthwave blended with contemporary pop. FM-84 and Ollie Wride, 2019

This pop-flavored evolution of synthwave is a colorful and lush style of music with fluid rhythms, bright synthesizer tones, and powerfully emotive vocals with strong melodic hooks. It differs dramatically from the mechanical beats, sparse compositions, and robotic vocal delivery of synth pop music, and the two styles are fundamentally unrelated.

In fact, it’s increasingly accurate to think of this music as a subgenre of contemporary commercial pop. Aside from its retro synth tones, “Bend and Break” has a strikingly similar feel to The Jonas Brothers’ “I Believe,” also from 2019.

‘10s commercial pop. The Jonas Brothers, 2019

To further illustrate this creative divide, it’s worth comparing “Bend and Break” side-by-side with a retro synth pop creation from the same decade. And One’s “Dancing in the Factory” from 2011 is a true synth pop track unmistakably written and performed in the style of early Depeche Mode creations like “Just Can’t Get Enough.”

A true synth pop track in the modern era. And One, 2011

“Dancing in the Factory” can be tied directly to pioneering synth pop creations and is a synth pop song in the fullest sense possible. In contrast, it would be necessary to backtrack through numerous genres, eras, and several branches of post-synth pop evolution to begin to connect FM-84’s music to the roots of the synth pop genre. Those tangled and numerous degrees of separation make it impossible to classify songs like “Bend and Break” as synth pop.

FM-84, The Midnight, The Bad Dreamers, and dozens of others are innovative and pioneering acts forging an exciting and increasingly popular style of synth-based music worthy of new terms and new discussions about synthwave. However, if a general or broad term is needed to describe the music in casual conversation, it is much more relevant and less confusing to simply call their creations “pop music” or “mainstream pop” instead of synth pop, as they share much stronger similarities with commercial genres of the past decade than with any form of synth pop or other music from the 1980s.

On the other hand, if generalities are to be avoided, fans, journalists, and artists should embrace more specific, relevant labels like “synthwave,” “pop synthwave” or a new term that does not already have decades worth of deep, concrete associations attached to it for millions of listeners.

There’s Some Overlap Between Synthwave and Synth Pop, Right?

Absolutely. As with nearly all genres, there is some overlap in styles between synthwave and synth pop, and there are clear examples of music that can be accurately classified within both genres. In these cases, it is predominately the songwriting and performance of the music that makes it synth pop while the retro synth tones and other throwback production touches shift it into the realm of synthwave.

Mecha Maiko is one of the few artists making a hybrid form of synth pop and synthwave. “Electric Heat” from her 2018 solo album Mad But Soft contains the industrial-tinged percussion, stiff rhythms, cold production, and reserved vocal tone that define synth pop music, and it easily falls within the same scope of music as all the synth pop songs discussed above, including tracks like Boytronic’s “You.” The artist's previous project, Dead Astronauts, also created numerous songs that can be accurately classified as both synth pop and synthwave, such as “Black Echo.”

Synth pop with synthwave production. Dead Astronauts, 2018

Many of the songs on Alex’s Simulations album from 2018 can also be properly classified as synth pop, particularly tracks like “Game Over” and “Random Access Fantasies.” In fact, these songs arguably have more in common with synth pop than synthwave. A high number of songs in Compilerbau’s discography are also fully classifiable as synth pop, including vocal tracks like “Talking Machines” (once again featuring the theme of sentient robots) and “Far Away.” Several Maxthor creations, particularly the artist’s collaboration with The Foreign on “The Streets of 1987, Pt. 2,” blend the songwriting and delivery of synth pop music with synthwave production. Notice the robotic vocal delivery, minimal rhythm, and quick snap of the percussion in the song below.

Synth pop with synthwave production. The Foreign and Maxthor, 2015

These creations and similar ones constitute a relatively small slice of synthwave, and roughly five percent or less of synthwave creations could be classified as any form of synth pop music. Generally speaking, synth pop and its defining characteristics are absent from the broader synthwave genre.

On a related note, however, the widespread revival of post-punk and dark wave music currently underway contains many songs that can be properly classified as synth pop, such as “Geometric Vision’s “Jelly Dream” and Minuit Machine’s “Empty Shell.” This revival of music is much more closely related to synth pop than synthwave is, a fact that makes perfect sense from a historical perspective. She Past Away has produced numerous dark wave tracks with strong synth pop underpinnings over the past decade, and songs like “Katarsis” are an unmistakable modern example of dark wave and synth pop’s decades-long relationship.

Dark wave with a strong synth pop foundation. She Past Away, 2016

Although it’s true there are some gray areas between synthwave and synth pop, demarcation lines must exist somewhere, or else every song in the world becomes a synth pop song. Synthwave and synth pop have remarkably different characteristics and historical evolutions, and within the scope of synth-based music, are separate genres that often appeal to separate demographics of listeners.

To reiterate the analogy from earlier, they are much more like musical neighbors than housemates or family members.

Another look at the genre map from earlier reveals the pattern of evolution across genres through specific songs. Once again, it’s important to note that it’s impossible to fully classify music in this way, and so the song locations are approximations meant as a visual reference, not concrete categorizations.

Conclusion

Using the terms "synthwave" and “synth pop” interchangeably causes real confusion for listeners of both genres, complicating the process of connecting interested fans with artists they will enjoy. Synthwave has its own name and identifying characteristics, and there’s no need to retroactively borrow the name of a different and beloved genre of music. (Particularly as “synthwave” was already co-opted from a more loosely defined term for synthesizer music in the 1980s.)

This fact would’ve been true of synthwave five or six years ago, though it’s more relevant now than ever. Fans of the stark and often industrial-minded sounds of synth pop are not always likely to embrace the soft, rich, and sentimental music of artists like The Midnight and FM-84, whose vocal-driven compositions are a significant source of confusion over the name.

Like all aspects of language, the fundamental purpose of music genres is to help us identify our shared experiences and communicate ideas with one another. To that end, the goal is always to be as clear as possible, thereby minimizing confusion, improving comprehension, and most importantly, enjoying and sharing the music we love.

Synthwave and synth pop are distinctly different genres that occasionally mingle at their edges and are otherwise content to explore their own ideas. They are each unique and wonderful genres with thousands of contributing artists who have helped define the shape and substance of their individual styles, and they each deserve to have their names reserved for their specific creative approaches.